ОПИС | DESCRIPTION

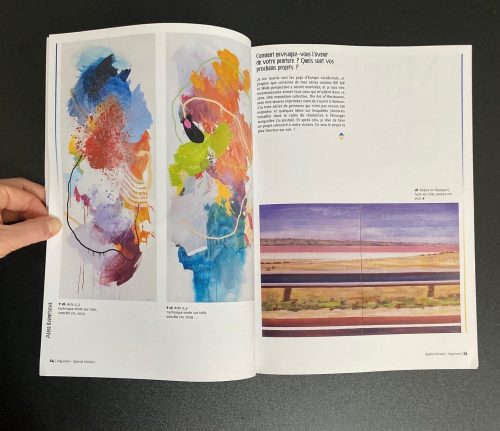

Назвa: “Act 2. 2” та “Act 2. 4” | Title: “Act 2. 2” & “Act 2. 4”

Серія: Механічний балет | Séries: Ballet mecanique

Художник: Альона Кузнєцова | Artist: Alena Kuznetsova

Розмір: 200*80 см | Size: 200*80 cm

Дата створення: 2019 | Date of creation: 2019

Місце написання: Київ | Place of creation: Kyiv

Тип: Картина | Type: Painting

Техніка: Змішана | Technique: Mixed

Материал: Полотно | Material: Canvas

Виставки: “Траєкторія” (2019), галерея Міронової (Київ), 2019

Exhibitions: “Trajectory” (2019), Mironova Gallery (Kyiv, Ukraine), 2019

Атрибути: Сертифікат автентичності | Attributes: Certificate of authenticity

Пакування: Картона чи дерев’яна коробка, Тубус | Packaging: Carton or wooden box, Tube

Ціна: За запитом | Price: On demand

Статус: Доступна | Status: Available

ТЕКСТ | TEXT

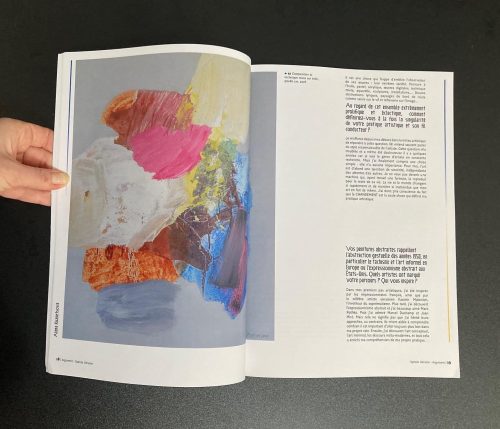

Серія “Механічний балет” є художнім дослідженням таких понять, як рух, динаміка, композиція, їх взаємодії та впливу на емоційні поля, створення певних настроїв, які народжуються при поєднанні або перетинанні траєкторій рухів окремих об’єктів, масс, особистостей.

Динамічний безпредметний живопис Альони Кузнєцової із серії «Механічний балет» своєю композицією, фактурою, поєднанням різних медіа (від акрилу до емалей та аплікації) нагадує незвичайну музику (механічну чи може електронну), яка своїм звучанням складає оригінальні траєкторії танцю, що триває не тільки в просторі, але й у часі.

Ця серія картин присвячена художньому однойменному фільму, задуманому, написаному та спільно зрежисерованому художником Фернаном Леже у співпраці з режисером Дадлі Мерфі, який містить музичну партитуру композитора Джорджа Антейла 1924 року.

This series of works by Alena Kuznetsova departs from the previous, completely dissolved, and tranquil liquid series and addresses the composition, graphics bordering abandoned esthetics, layers of lines, and planes. There, traditional color as an independent medium is subjected to the form and is essentially of secondary significance. It is a separate musical instrument in an orchestra: it just plays its part. Continuing the tradition of mixed technique, Alena takes these media apart into layers as the layers of memory, working without sketches and deciding at every stage on the choice of the next layer: acryl, oil, spray paint, oil pastel, enamel, and again acryl (the order may vary).

Ballet Mécanique movie is known for its radically repetitive style and instrumentation. The musical score for the film was written by composer George Antheil, combining atonal music and jazz rhythms. This film, included in the exhibition together with the documentation of the work process and the works of the artists themselves, creates a complex organism-orchestra that unites different eras, ideas, artistic expressions, and art forms.

ПУБЛІКАЦІЇ | PUBLICATIONS

ГАЛЕРЕЯ | GALLERY

ІМПЛЕМЕНТАЦІЯ | IMPLEMENTATION

Color as complete medium

Color as complete medium  Art and factory: look to the production

Art and factory: look to the production Art and nature have always found ways to intersect with one another, the latter being a huge source of inspiration for artists. Found across many forms: rural and historical for the Classicists, grandiose and wild for the Romantics, or sensitive and poetic for the Impressionists. But it was only much later that the artist became aware of the environment’s fragility.

Art and nature have always found ways to intersect with one another, the latter being a huge source of inspiration for artists. Found across many forms: rural and historical for the Classicists, grandiose and wild for the Romantics, or sensitive and poetic for the Impressionists. But it was only much later that the artist became aware of the environment’s fragility.